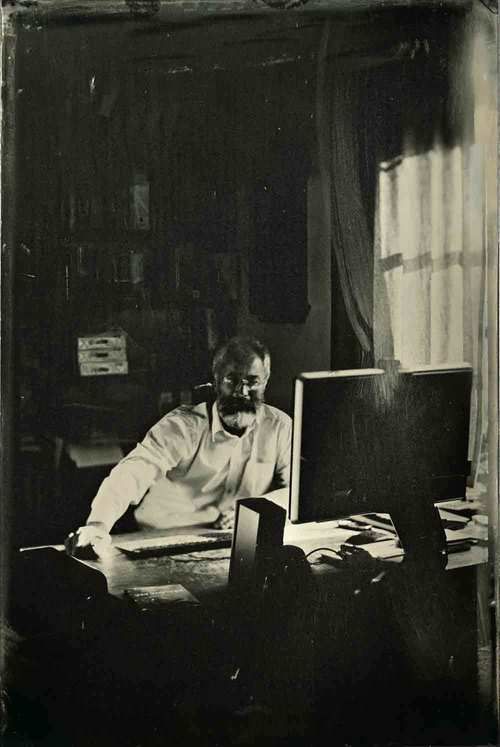

About author

I was born in 1954 in Prague to parents that, as it happened, came from Teplice (mother Erna, an English teacher) and from Vsetín (father Jaroslav J., graphic artist and painter). I grew up in the Lhota peripheries of Strašnice in a street that, at that time, was a safe, mysterious and secluded place with friendly neighbours. It seems insane today but, as a young boy, I walked home from kindergarten by myself two kilometres across the fields with a house key around my neck.

In addition to enjoyong the cycling stadium at Třeběšín, I fell in love with Křižany pod Ještědem, where my parents had bought a log cottage before I was born and before it became the fashion. The local boys are still my friends today.

Elementary school was without problems, but secondary school was not. I began to attend secondary school in 1969. Things became worse a year after the Soviet invasion and this was soon felt at the school. I was also entering puberty at the age of fifteen and this occupied me more than school. Of everything, the best were the week-long hop brigades in the spring (wiring) and in the autumn (picking). We had a great class and many of still us get together more than once a year. The teachers were less commendable. In any case, I graduated on the first attempt with miserable results and an even worse personal report. Of course, the class teacher didn’t show it to me, but one of the girls in my class told me about it. By chance I got a look at it when I was a temporary worker at the study department of the Faculty of Journalism of Charles University, where I had submitted an application. I remember only the comment “Watch out – father”. With watchoutfather (and certainly also with my graduation results), they did not accept me. I started work at CTK at the telex, where I tore off news reports that poured out of the machine and took them next door to the shift workers for approval. This was to be my journalistic training at CZK 800 per month before taxes, which I hoped would get me into journalism in a year’s time. I was lucky; in two months’ time they transferred me to the Prague editorial room and entrusted me with news about traffic, derailed trams, broken legs, weeks of Bulgarian cooking and other important news items. At CTK I learned not only to type rapidly, but also to manage this under the machine-gun fire of dozens of mechanical typewriters on which my colleagues were bashing out their own reports in the newsroom.

After two years (and two more unsuccessful attempts to be accepted by the Faculty of Journalism of Charles University), my supervisor arranged a meeting for me with her husband, JUDr. Karel Helmich, the Secretary of Světa motorů (the World of Motors magazine). They happened to have a free position and accepted me. Here I must mention the editor-in-chief of Světa motorů, Mirosloav Ebr. Not that he didn’t have his drawbacks, but employing a twenty-two-year old cub with fours on his graduation certificate and two years of experience was a brave deed on his part. In his place I wouldn’t do it.

The people at Světa motorů were a good bunch and I found my milieu there. It should be pointed out that Světa motorů was a prestigious magazine at that time with 360,000 copies printed every week. I continued to apply for university. When I received the fourth rejection, I wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, the Presidium of the Government and the Ministry of Education, saying that I wanted to know why I couldn’t study what was already my profession. No answer. However, at the next examinations, they didn’t ask me anything and accepted me. They probably received an instruction that there are no problems with the troublemaker. Now that was study! For example, scientific atheism was read from a paper by a woman with the accent of a Žižkov concierge. Or an assistant professor who married a Russian and, to make sure, took her surname or ... There were a number of excellent people among my fellow students, such as Honza Jiříček, who managed cover up the fact that he had been one of the founders the Club of Committed Non-Party Members – KAN in 1968. This was an organization that was so unacceptable to the Communists that, at Světa motorů, we were not allowed to write about the Hradec Králové automobile of Alois Nejedlý from the time before the First World War – because it had the brand KAN stamped on the radiator.

I got married in 1980; my wife Eva is a physician who devotes herself to treating dependence on tobacco. Our son Honza was born in 1983 and is now also a father (Adam, 2011). He studied at the Literary Academy of Josef Škvorecký, is self-employed and works at something he can’t describe, but he looks like he enjoys it and seems to be satisfied.

I completed university studies with fewer problems than secondary school. I remained in the editorial room of Světa motorů for nine years, until 1984, when they suggested I apply for membership in the Communist Party for the third time. So I left.

I accepted a position at NADAS, the Publishing House of Transport and Communications, in the promotion department as the only employee. It was the worst year in my professional career, because there was nothing for me to do there. NADAS issued a timetable once a year, printed train tickets on cardboard and occasionally issued a publication. We didn’t see eye-to-eye with the manager, so the first book that I published there (Steam Symphony) had to be signed with the name of my colleague as author and the second (And it Really Does Turn Round) was published five years after I handed in the manuscript and when I had left long ago.

I survived there for one year during, which I expended all my efforts to ensure I could be self-employed. At that time, this was practically ruled out, impossible, was fundamentally not permitted. Thus, I have been self-employed since September of 1985.

At the end of 1984, I managed the magazine Auto&moto veterán, which was created as “a methodical handbook for directing the work of ZO Zväzarm (Basic Unit of the Slovak Union for Cooperation with the Army) in the professional field of historical vehicles, intended for internal use by ZO Zväzarm”. At that time, it was a crime to publish an unofficial magazine. However, a methodical handbook for the Slovak basic organization of Svazarm, which had about 20 members, was possible. The Union for Cooperation with the Army was a semi-military organization, under whose wing the veteran fans could hide. The “Handbook” for the small club was published for three years, on chalk paper with a coloured jacket, with a print run of up to 2000 copies.

In 1985, I began to work with Studio Shape, a group of creative artists, architects and screenplay writers. They won a competition for the central pavilion for Expo ’86 in Vancouver in Canada. It was my task to find the most interesting exhibits at the accessible European and American technical museums.

I worked as a self-employed journalist for Technický magazín (an excellent monthly) and the Czechoslovak Motor Review, which was published in several languages. Through happy circumstances and coincidences (and also thanks to the Editor-in-Chief of CMR Jiří Hájek), I went to the Paris-Dakar Rally in 1988, when Karel Loprais first won in the category of trucks. That was a marvellous experience.

In 1990, I began to work in one of the first advertising agencies. Studio Shape became the representative of the international agency Saatchi & Saatchi. This was completely new and interesting. Two years later, I moved to the Studio Beam agency and remained there until 2000 (Mainly thanks to its manager, Ing. Honza Vávra). At that time I finally left the world of advertising with a feeling of relief (but did not part ways with Honza). I worked in advertising as a creative manager, I can remember only an animated television commercial for the Philishave shaver “Proletarians of the World, shave right!”, in which we removed the beards of Lenin, Marx and Engels and for which Pavel Koutský and I received the Louskáček prize – or what was it called?

In the meantime, I wrote booklets and fell in love with historical velocipedes. In 1987, I managed to get through the barbed wire to Holland for three days to attend a meeting of velocipede collectors. And that was that. I exchanged the few historical motorcycles that I had in various stages of decomposition for bicycles. In 1993, together with some friends, we held the International Veteran Cycle Association Rally in Prague, which was attended by 350 enthusiasts from around the world. And thus we were accepted by this international family. In the same year, some friends and I resuscitated the Czech Velocipedist Club 1880, the oldest of its kind in Central Europe, which had been suffocated by socialist physical training in the 1950’s. The renewed CCV 1880 is best known for its “whirls” – artistic choreography on high-wheel bicycles to the notes of the Prelude to Rossini’s opera The Thieving magpie. This has cost us considerable efforts and bruises.

I have frequently attended the International Cycling History Conference with lectures on the history of cycling and production of bicycles. In 2010, with the assistance of friends from the Czech Velocipedist Club, The First Czech Museum of Cycling and the National Technical Museum, we held this conference in Prague. I work closely with NTM and administered the cycling exhibits there in the early 1990’s; in 2011 I arranged the exhibition of bicycles in the newly opened transport hall. I am a member of the scientific council and chairman of the editorial board.

From the very beginning, I have cooperated with the Paraple Centre (for handicapped people); in fact this began even before the organization was established. The technical magazine published my report on people in wheelchairs, which came out at the end of the socialist experiment. There were some difficulties associated with it because parts were read out in dissident broadcasting. So I acquired a number of good friends.

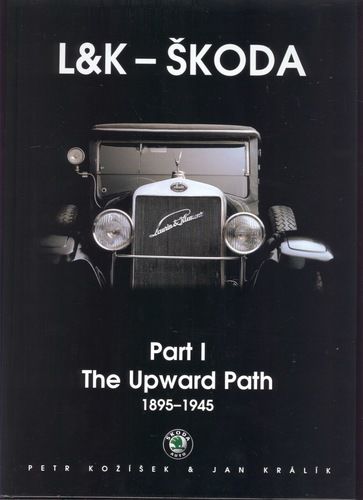

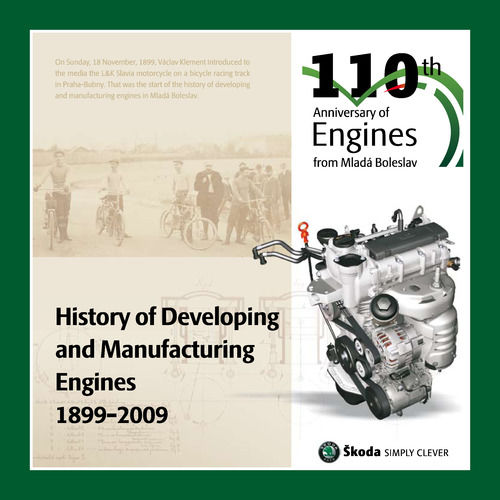

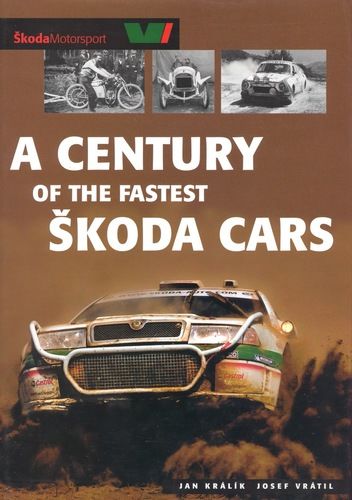

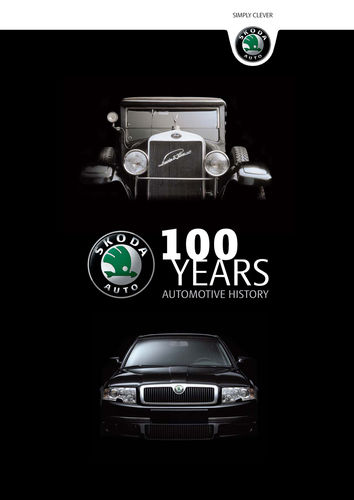

In 1993 I prepared the Czech part of the European exhibition on the development of the bicycle at the Austrian castle of Schwarzenau, with participation by foreign collectors and several museums. In the same year, I prepared an exhibition of American bicycles from the Dutch Velorama museum at NTM. In 2001, I prepared the scenario and produced the exhibition One Hundred Years of Motorism as an event accompanying Autosalon Brno 2001. In the same year, I also worked similarly on the exhibition Bicycle in all Ways, as an event accompanying the Sportlife Brno trade fair. How the Automobile is Born was an exhibition that I prepared for Autosalon Brno 2003. In 2005, I worked as a scriptwriter for the exhibition 100 Years of the History of L&K-Škoda Automobiles. In 2004 and 2005, I was president of the International Veteran Cycle Association.

Since it began to be published, I have regularly contributed to the Motor Journal magazine and am a member of its editorial board.

Whenever possible (and, if you want to, it is always possible), I sit on a bicycle, high-wheel or ordinary, it doesn’t matter, but I prefer if it has a history. I mostly ride a road bicycle fitted with a Dura Ace derailleur originally owned by my friend Jarda Majer, who is unfortunately no longer with us. And thus, even when I ride by myself, I am not alone.